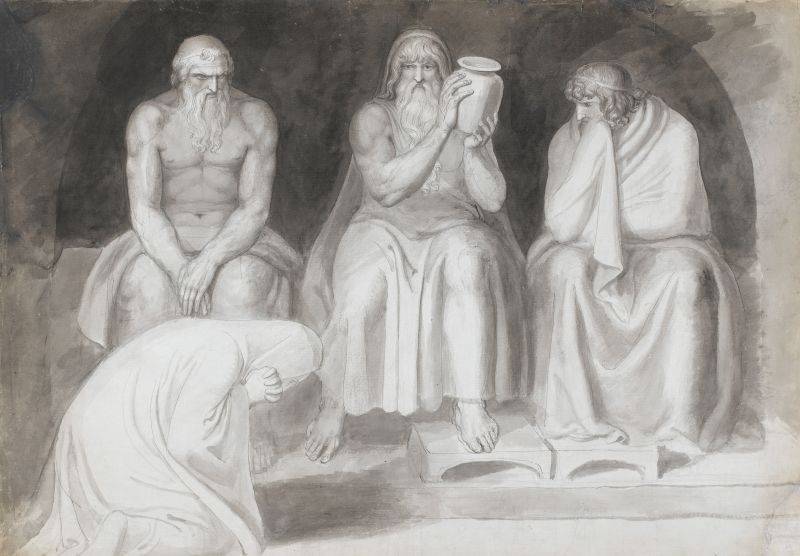

This monumental monochrome drawing was made by John Flaxman in 1783. Previously unknown and unpublished, the sheet belongs to a group of large, finished drawings made before Flaxman travelled to Italy. Highly sculptural in feel, the composition depicts an episode from the Old Testament, Hannah presenting her son Samuel to the prophet Eli and ranks as one of Flaxman’s most ambitious early works.

Flaxman was the son of a professional sculptor and he received his earliest education in his father’s Covent Garden shop and studio. Flaxman’s early prodigious talents as a draughtsman attracted the attention of two of his father’s professional contacts, George Romney and Josiah Wedgwood, both of whom became important supporters. In 1770 Flaxman entered the Royal Academy schools, where, according to an early biographer, Allan Cunningham:

‘he was known at the academy as an assiduous and enthusiastic student… his chief companions were Blake and Stothard: in the wild works of the former he saw much poetic elevation… with Blake, in particular, he loved to dream and muse, and give shape, and sometimes colour, to those thick-coming fancies in which they both partook.’[1]

Whilst Cunningham’s chronology is a little confused, Blake did not enter the Academy schools until 1779, the friendship between the two artists in the early 1780s was of profound importance for both men. Flaxman’s most compelling finished drawings in this decade share certain stylistic qualities with those by Blake of the same date. Flaxman and Blake were both supported by the Reverend Anthony Mathew and his wife, Harriet. J.T. Smith records that the Mathews’ house, 27 Rathbone Place, ‘was then frequented by most of the literary and talented people of the day.’[2] The Mathews, with Flaxman’s assistance, helped Blake to publish his Poetical Sketches in 1783 and Cunningham credits Harriet Mathew with encouraging Flaxman’s interest in ancient texts: ‘Mrs Mathew read Homer, and commented on the pictorial beauty of his poetry, while Flaxman sat beside her embodying such passages as caught his fancy. Those juvenile productions still exist and are touched, and that not slightly, with the quiet loveliness and serene vigour manifested long afterwards in his famous illustrations to the same poet.’[3]

Blake and Flaxman shared an interest in the gothic. Blake had been apprenticed to the engraver James Basire who sent Blake to Westminster Abbey to make drawings of the medieval monuments and wall paintings. As Benjamin Heath Malkin noted the sculpture filling the abbey ‘appeared as miracles of art, to his Gothicised imagination.’ Flaxman in turn, seems to have assiduously studied medieval art. Smith notes that in gratitude for all the support he had received from the Mathew family, Flaxman ‘decorated the back parlour of their house, which was their library, with models, (I think they were in putty and sand,) of figures in niches, in the Gothic manner; and Oram painted the window in imitation of stained-glass; the bookcases, tables, and chairs, were also ornamented to accord with the appearance of those of antiquity.’

The present work belongs to a small group of large-scale drawings made by Flaxman in the early 1780s. They do not appear to have been commissioned or form any coherent iconographic scheme, but they demonstrate Flaxman’s remarkable powers as a designer, each showing a series of monumental figures, drawn in Flaxman’s characteristic assured ink line and modelled in wash. The present drawing depicts a scene from the Book of Samuel, Hannah is seen presenting her infant son Samuel to the priest Eli to be brought up as a Nazarite. This was a subject which had been treated by both Benjamin West in 1778 and John Singleton Copley in a painting completed in 1780. But Flaxman’s treatment of the subject is radically different; Flaxman presents the four main characters in a frieze-like arrangement. Eli stands in profile one hand holding that of the infant Samuel, his other raised to the sky, a gesture that foreshadows Samuel’s portentous communications with God. It is to the young Samuel that God speaks, informing him that Eli and his children will be punished for their poor behaviour. Hannah stands apart, in the centre of the composition, Flaxman renders her as an elegant gothic Madonna with delicately elongated fingers, on the right is her husband, Elkanah shown with a highly sculptural cloak drawn about him. Flaxman’s precise, sinuous pen work and delicate washes rendering the four figures like a series of freestanding statues in a niche.

These grand monochrome studies recall the work of Blake at the same moment. In the mid-1780s Blake was working on illustrating the first of his prophetic books, Tiriel and it is clear that Blake was drawing on similar source material. The Tiriel illustrations adopt the same frieze-like format and marmoreal draperies, reminiscent of medieval sculpture. But whilst Blake’s designs contain a certain awkwardness, Flaxman’s mastery of pen ink means that this composition is full of his characteristic ‘quiet loveliness and serene vigour’ noted by Cunningham. Flaxman’s sheet also demonstrates his power as a designer, each figure mutely conveying the essence of the story of Samuel.

John Flaxman

A soul appearing before the Judges of Hades

19 ¼ x 27 ⅜ inches; 490 x 697 mm

Graphite, pen and ink and grey wash on laid paper, laid down

c. 1783

© Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge

References

- Allan Cunningham, The Lives of the Most Eminent British Painters, Sculptors and Architects, London, 1830, vol.III, p.283.

- J.T. Smith, Nollkens and his Times: Comprehending a life of that celebrated sculptor; and memoirs of several contemporary artists…, London, 1828, vol.II, p.455.

- Allan Cunningham, The Lives of the Most Eminent British Painters, Sculptors and Architects, London, 1830, vol.III, p.281.

- J. T. Smith, A Book for a Rainy Day, London, 1845, p.83.