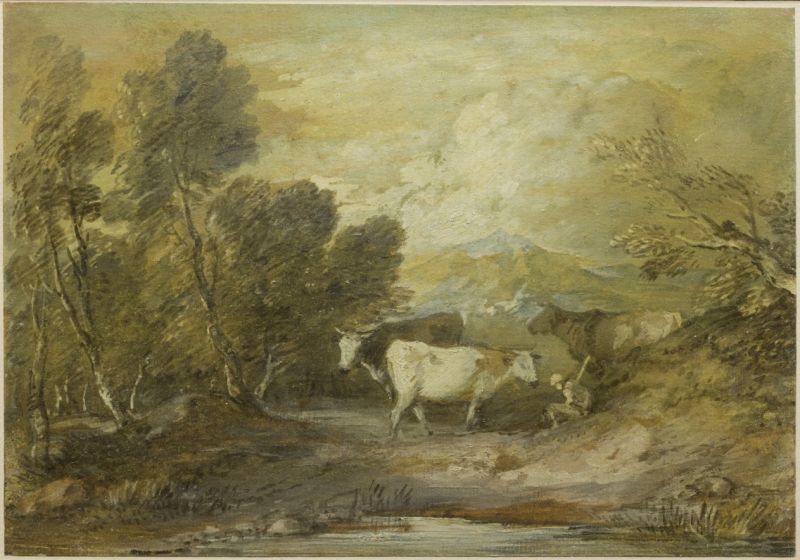

This refined varnished mixed-media drawing was made by Gainsborough in Bath in the early 1770s; an experimental process, these rapidly worked, highly evocative sheets underline Gainsborough’s deeply personal engagement with the processes of landscape drawing. Gainsborough’s varnished drawings also acted as vehicles for his experimentation with both techniques and materials. The method used in this drawing was outlined in a letter which gives a sense of his innovation. We know from contemporaries that these ambiguous drawings, translating the boundaries between drawing and painting, devoid of specific narrative, were highly prized by collectors and keenly discussed as works imbued with feeling. This sheet comes from an exceptional group of fourteen drawings Gainsborough gave to his friend Goodenough Earle of Barton Grange, Somerset. This carefully assembled series of drawings have long been recognised as consisting of Gainsborough’s personal survey of his most refined work as a landscape draughtsman. As such, this concentrated, varnished sheet, belongs to a particularly important and well documented group of Gainsborough’s landscape drawings and is an unusually bold, sophisticated and attractive example.

Gainsborough’s own description of producing varnished drawings such as this is contained in a letter dated 29 January 1773 written to his friend William Jackson. Jackson, an amateur landscape painter himself, had evidently asked for Gainsborough for his method. Gainsborough warned him that: ‘There is no Man living that you can mentions (besides your self and one more, living) that shall ever know my secret of making those studies you mention.’[1] He then explained:

'take half a sheet of blotting paper such as the Clerks and those that keep books put upon writing instead of sand; ‘tis a spongy purple paper. Paste that and half a sheet of white paper, of the same size, together, let them dry, and in that state keep them for use – take a Frame of deal about two Inches larger every way, and paste, or glue, a few sheets of very large substantial paper, no matter what sort, thick brown, blue, or any; then cut out a square half an inch less than the size of your papers for Drawing; so that it may serve for a perpetual stretching Frame or your Drawings; that is to say after you have dip’t your drawings as I shall by & by direct in a liquid, in that wet state you are to take, and run some hot glue and with a brush run round the border of your stretcher, gluing about half an Inch broad which is to receive your half an Inch extraordinary allow’d for the purpose in your drawing paper, so that when that dries, it may be like a drum. Now before you do any thing by way of stretching, make the black & white of your drawing, the Effect I mean, &disposition in rough, Indian Ink shaddows & your lights of Bristol made white lead which you buy in lumps at any house painters; saw it the size you want for your white chalk, the Bristol is harder and more the temper of chalk than the London. When you see your Effect, dip it all over in skim’d milk; put it wet on [your] Frame (just glued as before observed to) let it dry, and then you correct your [illegible] with Indian Ink & if you want to add more lights, or other, do it and dip again, till all your Effect is to your mind; then tinge in your greens your browns with sap green & Bistre, your yellows with Gall stone & blues with fine Indigo.'[2]

Gainsborough finally observed: ‘varnish it 3 times with Spirit Varnish such as I sent you; though only Mastic & Venice Turpinetine is sufficient, then cut out your drawing but observe it must be Varnished both sides to keep it flat.’

The present sheet, probably made in about 1772, precisely represents this process. The letter is remarkable because it suggests both Gainsborough’s level of inventiveness, awareness of materials – note his use of paper not designed for drawing – and pursuit of innovative techniques to create novel effects in his landscape compositions. Gainsborough has used an off-white paper and then built up the composition, first adding the lead white, to lay in the white horse and side of the buildings and highlight on the fallen tree trunk in the foreground. As the letter suggests this was not chalk, technical analysis undertaken by Jonathan Derow of other varnished drawings has proved that it was dry white pigment, consistent with the Bristol lead white mentioned by Gainsborough.[3] The drawing could then be dipped in milk and washes applied to build up the landscape. This gradual process can be seen throughout the composition, which is made up of complex washes of watercolour articulated with pen and ink.

The motif of the drawing – riders on a country road - is typical of Gainsborough’s landscape drawings and raises the question of its appeal to contemporaries. His varnished sheets – some measuring over a metre in length – occupied an unusual place in Gainsborough’s extensive oeuvre, being, as he stated, prepared for exhibition at the Royal Academy. Whilst the present sheet seems unlikely to have been prepared with exhibition in mind, its presence amidst the highly edited group of drawings Gainsborough presented to Goodenough Earle marks it out as an exceptional example of its type.[4] The appeal of Gainsborough’s varnished drawings lay in part in their relationship with Dutch seventeenth-century landscapes. From early in his youth Gainsborough had been fascinated by the works of Salomon van Ruysdael, Aelbert Cuyp and Jan van Goyen; the muted palette and simple arrangement of cattle in an open landscape particularly recalls fashionable Dutch prototypes. But there is also evidence that contemporaries read something more immediate and emotional in Gainsborough’s landscapes. The mood of such drawings was well described by Edward Edwards in his Anecdotes of Painters: ‘in his latter works, bold effect, great breadth of form, with little variety of parts, united by a judicious management of light and shade, combine to produce a certain degree of solemnity. This solemnity, though striking, is not easily accounted for, when the simplicity of materials is considered, which seldom represent more than a stony bank, with a few trees, a pond, and some distant hills.’[5] It was this imperceptible feeling of ‘solemnity’ which probably explained the success of a sheet such as this. There is growing evidence that Gainsborough, in common with his contemporaries, such as Alexander Cozens, was conscious of the ability for his landscape drawings to suggest certain emotions.

The 14 drawings Gainsborough assembled and gave to Goodenough Earle are central for establishing our understanding of Gainsborough’s own attitude towards his drawings.[6] We have no evidence that Gainsborough marketed his landscape drawings in his own lifetime, rather they existed in an economy of exchange and friendship, with Gainsborough’s closest friends receiving carefully selected groups. What makes the group given to Goodenough Earle so exceptional is that they were drawn from across Gainsborough’s career and include exceptional early works from the 1750s, such as the highly finished drawing of a market cart (National Gallery of Art, Washington) and watercolour of a Woodland Scene of about 1760 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). The group were exhibited by Knoedler in New York in 1914 and principally acquired by distinguished American collectors and a majority have subsequently been acquired by American museums.

This varnished drawing should be regarded as an exceptional work, not only within Gainsborough’s oeuvre, but in our understanding of the development of landscape drawing in Britain during the eighteenth century. In the present sheet Gainsborough combines the simple compositional motifs learnt from Dutch seventeenth-century painters with an emotional ambiguity which would become central to the art of Romanticism.

Thomas Gainsborough

Rocky landscape with cattle

Black chalk, watercolour and oil, varnished

8 ⅜ x 12 inches; 213 x 306 mm

1770-75

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Thomas Gainsborough

A herdsman with three cows by an upland pool

Watercolour, ink and oil paint heightened with Bristol lead

white

8 ⅝ x 12 5/16 inches; 219 x 313 mm

Cleveland Museum of Art (formerly with Lowell Libson Ltd)

References

- Ed. John Hayes, The Letters of Thomas Gainsborough, New Haven and London, 2001, p.110.

- Ed. John Hayes, The Letters of Thomas Gainsborough, New Haven and London, 2001, pp.110-111.

- Jonathan Derow, ‘Gainsborough’s Varnished Watercolour Technique’, Master Drawings, vol.26, no.3, 1988, pp.259-71.

- Gainsborough showed two large varnished landscapes at the Academy in 1772, traditionally identified as the ‘Cartoon’ now at Buscot Park and the large drawing at Yale; but the same year he also showed: ‘Eight landscapes, drawings, in imitation of oil painting.’ For the mention of Johan Zoffany couriering drawings from Bath to London see [1] Ed. John Hayes, The Letters of Thomas Gainsborough, New Haven and London, 2001, p.94.

- Edward Edwards, Anecdotes of Painting, London, 1808, p.139.

- See John Hayes, ‘The Gainsborough Drawings from Barton Grange’, The Connoisseur, vol.CLXII, 1966, pp.86-91.