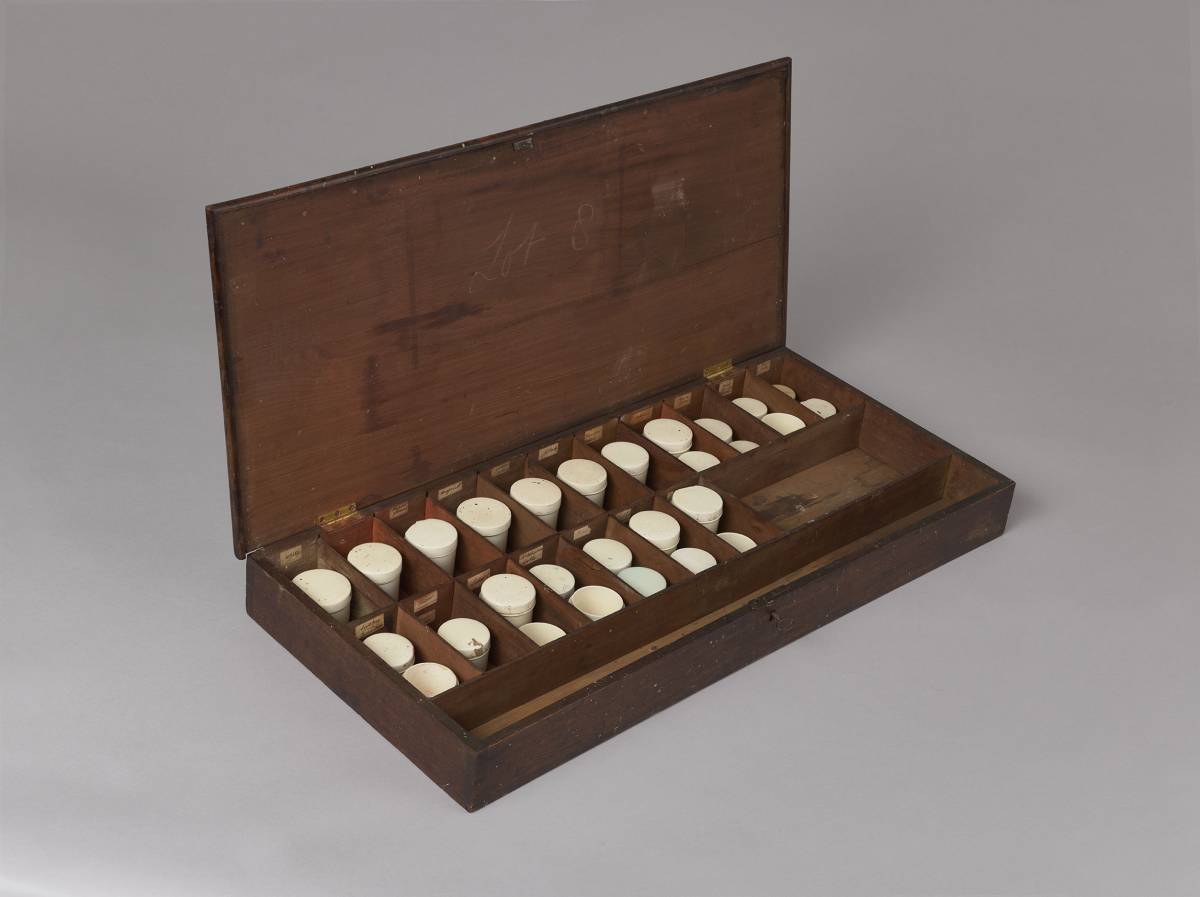

‘Lot.8 - A mahogany case, in divisions, with forty-four small pots, of various colours, and five dozen brushes.’

This remarkable mahogany paintbox is an exceptionally rare survival. Very little artistic apparatus used by professional painters in early nineteenth-century Britain survives and no comparable large-scale paintbox, with associated pigment pots is currently known. What makes this paintbox all the more remarkable is that it is documented as belonging to the leading portraitist operating in early nineteenth-century Europe, Sir Thomas Lawrence. The box is inscribed in chalk on its lid ‘Lot 8’ and can be linked directly to an entry in the posthumous Christie’s sale of the ‘valuable assemblage of casts…and the Painting Implements and Colours’ of Lawrence held in July 1830. Lot 8 is described as: ‘A mahogany case, in divisions, with forty-four small pots, of various colours, and five dozen brushes.’ The paint box survives, complete with paper labels inscribed with the names of pigments originally contained in each compartment, along with twenty-eight of the forty-four creamware pots. In addition, the paintbox contained a glass phial of ‘Spirit Turpentine’ with the label ‘Brown 163 High Hoborn’. Thomas Brown was known to have been Lawrence’s colourman with premises at the St Giles end of High Holborn not far from Lawrence’s studio in Russell Square.

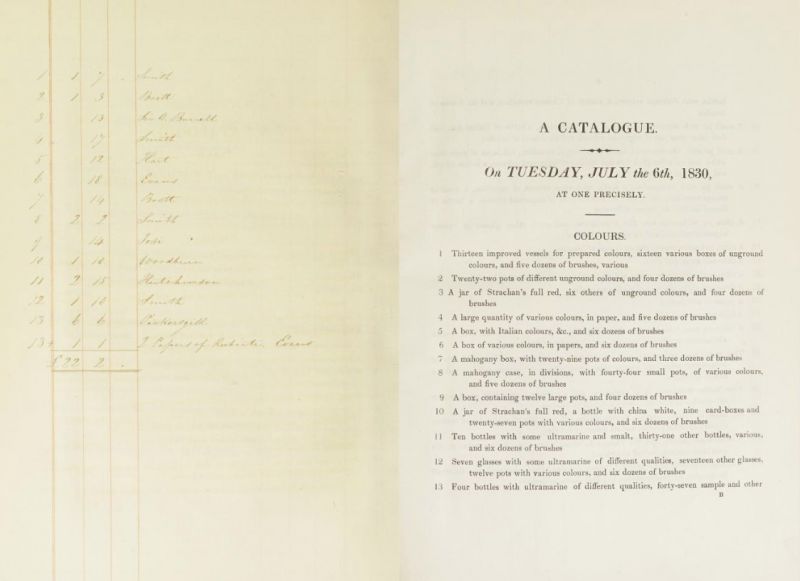

‘A Catalogue of a Valuable Assemblage of Casts…, and the painting Implements and Colours; and some Gold, Silver and Copper Medals, The Property of Sir Thomas Lawrence’, Christie’s, 6th July 1830.

Most of the surviving British artist’s materials from the early nineteenth century were those designed to be portable. The Turner bequest contains a series of boxes and pigments that came from Turner’s studio, housed in compact, transportable boxes, in addition the Royal Academy owns several palettes associated with William Hogarth, Joshua Reynolds and John Constable; but the present, substantial paint box, with ceramic pots for pigments, is a singular survivor. We know the appearance of Lawrence’s painting room thanks to a remarkable drawing made by Emily Calmady in 1824. The drawing, now in the collection of the Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, shows the painting studio at 65 Russell Square. Calmady captures the sense of the working space of a busy portraitist; she shows Lawrence working, reflected in a full-length cheval mirror. To one side is a Pembroke table covered in dozens of brushes of varying thickness. The shutters on the lower-half of the windows shut, to create the diffuse light recommended for portraiture. Ranged in front of the windows are a sideboard and chest of drawers, the sideboard appears to have been customised with two lidded compartments, with a space in the middle possibly to mix paint. It is probably identifiable in Lawrence’s studio sale as lot.42 ‘a mahogany sideboard, with a glass slab and muller, and doors and drawers.’ Calmady’s drawing shows lots of small pots of pigments scattered across the surfaces. These were likely housed in the present mahogany box and another listed as lot.7 in the studio sale ‘A mahogany box, with twenty-nine pots of colours, and three dozen brushes.’ Presumably the paintboxes and other studio furniture was specifically made for Lawrence, with fitted divisions to contain both pigment pots and brushes.

Emily Calmady

Sir Thomas Lawrence's Painting Room in 1824

Graphite and white gouache

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Fund, B2006.6.

As Jacob Simon has noted, there has been comparatively little research done into Lawrence’s use of materials.[1] What evidence we have comes from disparate archival sources, rather than sustained technical analysis. From about 1810 he maintained a relationship with George Field, the leading experimental chemist engaged in preparing colours. Lawrence was interested in new colours, but cautious of their effect, so he wrote to Field asking him to test pigments he had brought back from Rome, from Anton Raphael Mengs’s paintbox, in 1820. Field replied:

‘I have done so to my entire satisfaction. The Red I find to be a Sulpheret of Mercury or Cinnabar, having all the qualities of the best Vermilion. The two others are Sulpherets of Arsenic of Realgar which have all the properties of orpiment in painting. They differ however considerably from those pigments as we usually fine them, and as Mengs was addicted to Chemistry I think it probable they may have been his own productions. And no doubt it may be possible to re-produce them.’[2]

Field proceeded to do so, and in a later note of his recipe he stated that it was Lawrence who had prevailed upon him, since this range of colours ‘afforded pure and truer flesh tints than he could form with his usual pigments.’ Lawrence purchased pigments from a number of different London suppliers including Smith, Warner & Co of 211 Piccadilly and Charles Roberson at 54 Long Acre. Lawrence’s posthumous sale suggests that he kept large stocks of ground pigment in his studio. The fitted interior of this paintbox is organised with 16 paper labels inscribed with a range of pigments. These include: white, Naples yellow, massicot, yellow ochre, ochre, Flanders ochre, ochre, Terra di Sienna, burnt Terra di Sienna, brown, pink, light red and India red, umber and burnt umber, lake, Nottingham lake and blue. Many of the creamware pots contain additional traces of pigment which could offer further avenue for analysis and research.

Lawrence used linseed oil to mix his paints, using the ‘Spirit of Turpentine’ found in the box for varnishing. If Lawrence could not supervise the process of varnishing himself, he would provide detailed instructions. Lawrence wrote in 1810 on sending a painting to America that ‘it should be varnish’d with the best Mastic Varnish… The brush should be a soft flat brush and it should be pass’d evenly downwards and across the picture thus + the operation is so simple, that any artist or picture cleaner knows perfectly well how to do it. The Mastic should be the purest picked gum dissolv’d in Turpentine.’[3]

Lawrence’s accounts with Charles Roberson show how much he spent on pigments. Their value is underscored by the prices lots of pigment achieved in the 1830 Christie’s sale. Lot.15 ‘a small jar with ultramarine, a bottle of extract of vermilion, a full jar of pure flake white, and six other glass jars and bottles of unground colours, a bottle of oil and six dozen brushes’ made £6. It is notable that other artists are recorded as purchasers, including Henry William Pickersgill and Frederick Richard Say both of whom acquired a number of lots.

References

- Jacob Simon, Lawrence’s materials and processes, online resource https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/research/programmes/artists-their-materials-and-suppliers/thomas-lawrences-studios-and-studio-practice/lawrences-materials-and-processes

- Quoted in John Gage, George Field and his Circle: From Romanticism to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, exh. cat. Cambridge (Fitzwilliam Museum), 1989, p.67.

- Kenneth Garlick, Sir Thomas Lawrence, Regency Painter, exh. cat. Worcester (Art Museum), 1960, p.38.