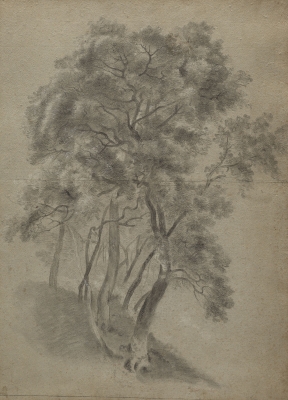

Made in the late 1780s, this highly expressive drawing ranks as one of Gainsborough’s most evocative final landscape studies. Rendered in black and white chalk on delicate, blue laid paper the drawing is preserved in exceptional condition. This sheet is unusual for having an eighteenth-century provenance, first being recorded in the collection of Gainsborough’s friend, and fellow founder member of the Royal Academy, Thomas Sandby. The drawing itself combines compositional motifs that appear in many of Gainsborough’s late drawings: a dense thicket of trees, sandy banks, a serpentine track and a donkey pulling a cart and its solitary occupant. These were elements Gainsborough continually returned to in his landscapes, combining and refining them to produce ever more complex and impactful works. This exceptional drawing belongs to a group of works on blue paper which appear, at first sight, almost unfinished, but which we know Gainsborough considered complete works of art. It was this group of enigmatic and apparently informal drawings, which were particularly in demand by contemporaries. Early commentators recognised the power of these ‘thoughts, for landscape scenery’ and explicitly linked them to newly codified aesthetic concepts, such as the sublime. As such, this sheet demands to be read, not within the rather limited context of eighteenth-century British landscape drawing but within the broader context of European Romanticism, where landscape was explicitly designed to elicit an emotional response.

The teleology constructed for British landscape drawing places Gainsborough as a somewhat awkward precursor to the great generation of British landscape painters of the nineteenth century. Awkward, because Gainsborough, unlike Turner, Girtin and Constable, eschewed actual views for landscapes of the imagination, however contemporaries understood and appreciated the power of his work. Writing in his Anecdotes of Painters published in 1808, Edward Edwards made an important early public assessment of Gainsborough’s late landscape drawings:

‘in his latter works, bold effect, great breadth of form, with little variety of parts, united by a judicious management of light and shade, combine to produce a certain degree of solemnity. This solemnity, though striking, is not easily accounted for, when the simplicity of materials is considered, which seldom represent more than a stony bank, with a few trees, a pond, and some distant hills.’[1]

This drawing perfectly encapsulates these qualities: Gainsborough has used black and white chalk on blue laid paper to create a strikingly simple composition, one that, despite the apparent simplicity of its subject, nevertheless has a profound emotional appeal. Edwards characterised Gainsborough’s late landscapes as ‘free sketches’ pointing to the fact that he developed a visual short-hand, particularly in his handling of trees, figures and cattle; the latter often appearing in an almost abstract reduction of shapes and lines. This virtuosic simplicity contributes to the powerful aesthetic of this sheet. Contemporary theories of aesthetic were exploring the potential of both the accidental line and judicious obscurity. Gainsborough deliberately leaves elements of the composition undeveloped, almost unfinished. Edmund Burke writing in his 1757 Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime, for example, specifically explained the appeal of certain types of landscape painting:

‘in painting a judicious obscurity in some things contributes to the effect of the picture; because the images in paintings are exactly similar to those in nature; and in nature dark, confused, uncertain images have a greater power on the fancy to form grander passions than those have which are more clear and determined.’[2]

In the present sheet, one might point to the mass of lines that construct the dense thicket of trees from which the donkey, cart and its driver have emerged, the lines making up the thick vegetation are consciously obscure. Masterfully applied, the black chalk lines collide and combine to give the sense of depth, whilst Gainsborough has left areas of reserve in the trees themselves, allowing the paper to show through and suggest the volume of the foliage. This obscurity in turn explains contemporary responses to Gainsborough’s late landscape drawings, particularly the ‘solemnity’ of Edwards.

Part of the ambiguity of Gainsborough’s composition is achieved by the seemingly random nature of his mark making. This was a process mythologised by later writers, Edwards called these late drawings by Gainsborough his ‘moppings’ – implying that they were the result of felicitous accidents - and later scholars have seen a parallel with the ‘blot’ method of Alexander Cozens. But this characterisation belies the careful structure of this drawing. Every line has been carefully and systematically applied and Gainsborough revels in the potential effects of his choice of media. On the right-hand side of the composition Gainsborough has used the laid lines of the paper to give a vertical structure to the distant, dissolving clump of trees, whilst the incline of the hill has been effectively suggested by lines of reserve, scored through the black chalk. Throughout the drawing touches of white chalk articulate the composition suggesting the fall of light from the left. It was the deceptive simplicity of this formula which prompted Joshua Reynolds to offer the audience of his Fourteenth Discourse a word of caution about Gainsborough’s technique, noting: ‘Like every other technical practice, it seems to me wholly to depend on the general talent of him who uses it… it shows the solicitude and extreme activity which he [Gainsborough] had about everything related to his art; that he wished to have his objects embodied as it were, and distinctly before him.’[3]

Scholars have long recognised that the motif of the solitary figure in a cart had a personal resonance for Gainsborough. In an oft-quoted letter to William Jackson, Gainsborough deployed the idea of the country cart in a complex metaphor for life. Having complained of the social whirl in Bath and the necessity of servicing his portrait practice, Gainsborough noted: ‘we must Jogg on and be content with jingling of the Bells, only d-mn it I hate a dust, the kicking up a dust; and being confined in Harness to follow the track, whilst others ride in the Waggon, under cover, stretching their Legs in the straw at Ease, and gazing at Green Trees & Blue Skies without half my Taste.’[4] Michael Levey was the first to suggest that Gainsborough’s drawings represent an ideal conceptualisation of this idea, Gainsborough escaping the necessity of his urban portrait business and enjoying the imaginative life of ease in the country. This idea of drawing as a form of escapism aligns with the eighteenth-century ideas of leisure. We know from several sources that Gainsborough made imaginative landscape drawings such as this in the evening. There is no contemporary evidence that Gainsborough sold his landscape drawings, instead they seem to have existed in an alternative economy of exchange, given to friends, collectors and patrons whom Gainsborough knew would appreciate their qualities.

In this context, the pleasure of viewing Gainsborough’s late drawings comes from a combination of factors. First the subject matter, contemporaries would have appreciated the contemplation of innocent rural life uncorrupted by urban manners and morals. Sensibility exalted feelings over the intellect as the true expression of a person’s innate morality, and there is no doubt Gainsborough saw himself as a painter of sensibility, once arguing that he always sought ‘a Variety of lively touches and surprizing Effects to make the Heart dance.’[5] A drawing such as this should also be viewed within the powerful contemporary market for old master drawings. There is growing evidence that drawings such as this were viewed as sophisticated essays on earlier old master drawing styles and that they directly appealed to those collectors who also acquired earlier works. Gainsborough’s use of Italian blue paper, his masterful use of black and white chalks recalls the landscape drawings of sixteenth-century Venetian artists. It is perhaps notable that this sheet is first recorded in the collection of the artist, collector and dealer Thomas Sandby who formed a notable collection of old master drawings. It has an exceptional later provenance passing from Sandby to the great nineteenth-century collector Charles Sackville Bale at whose sale it was acquired by John Postle Heseltine. Heseltine formed one of the greatest groups of old master drawings in the late nineteenth century, publishing 13 privately printed volumes celebrating masterpieces from his collection, this drawing appears in a volume published in 1902.

Thomas Gainsborough

Landscape with farm cart on a winding track between trees

Black and white chalks with stumping on blue paper

7 x 8 ½ inches; 182cm X 217 mm

Drawn c.1785

© Manchester City Galleries, 1953.1

References

- Edward Edwards, Anecdotes of Painting, London, 1808, p.139.

- Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, London, 1757, p.62.

- ed. Robert Wark, Sir Joshua Reynolds: Discourses on Art, New Haven and London, 1975, p.250.

- Thomas Gainsborough to William Jackson, year unknown, ed. John Hayes, The Letters of Thomas Gainsborough, New Haven and London, 2001, p.68.

- Thomas Gainsborough to William Hoare, 1773, ed. John Hayes, The Letters of Thomas Gainsborough, New Haven and London, 2001, p.112-113.

_1200_1108_70_faf9f5_s.jpg)

_160_148_70_faf9f5_s.jpg)