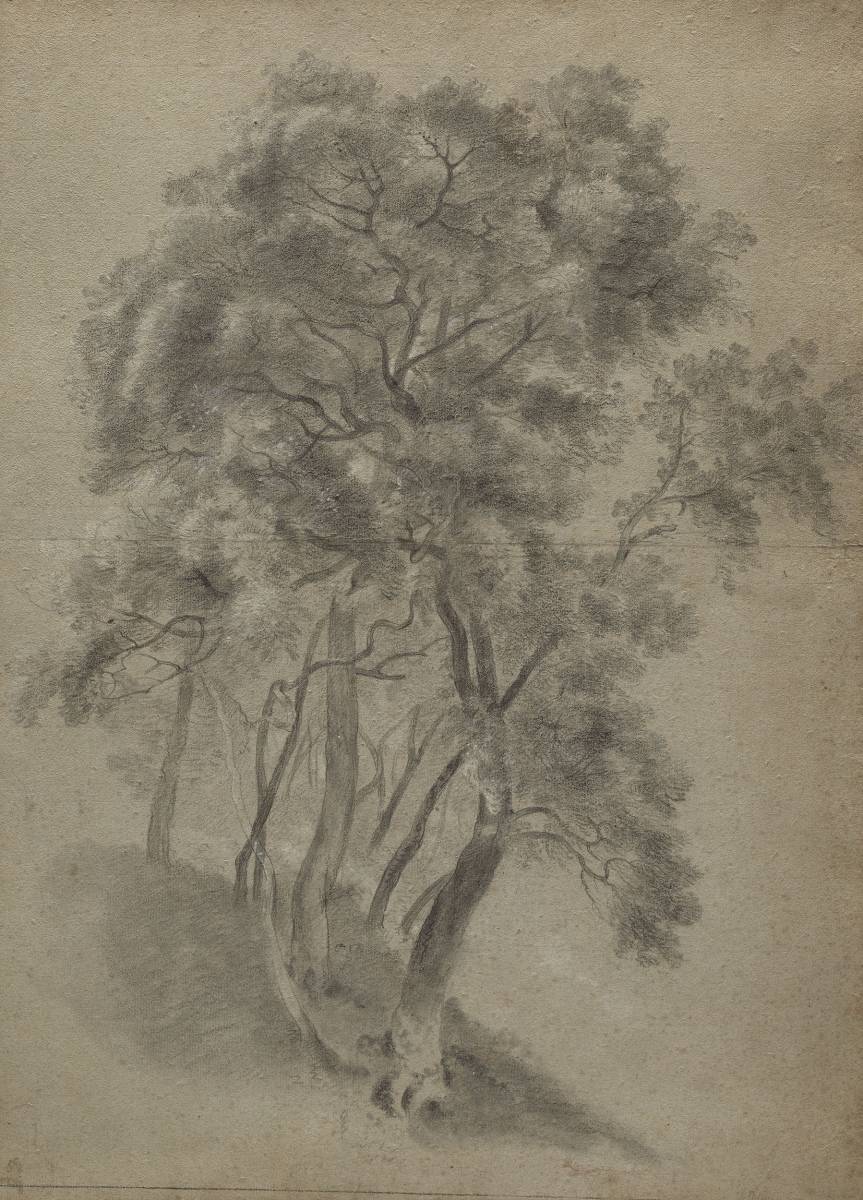

This is the largest and most ambitious plein air drawing made by Richard Wilson during his transformative stay in Italy. Executed in black chalk, heightened with white on grey, laid paper the drawing has an immediacy and freshness which is characteristic of Wilson’s rare nature studies. The delicacy and refinement of Wilson’s handling of the chalks points to the profound influence of French draughtsman working at the Académie de France à Rome. Wilson, documented as having been close to a number of French artists working in Rome almost certainly developed his approach to landscape drawing from them. But, unlike their carefully composed landscape studies, Wilson’s greatest drawings preserve both a sense of spontaneity and a fresh naturalism. This scrupulously observed study of a stand of chestnut trees was almost certainly retained by Wilson as reference for his finished landscapes and drawings, works which in their approach and execution defined a new approach to Grand Tour landscape and proved a model for a generation of European artists.

Richard Wilson was born in Montgomeryshire, Wales into a well-connected gentry family. As a young man he was apprenticed to the portrait painter Thomas Wright and following his apprenticeship he practiced as a successful portrait painter in London. In 1750, in his mid-thirties Wilson travelled to Italy, unusually he began his Grand Tour in Venice where he had letters of introduction to the British consul, Joseph Smith. It was in Venice that Wilson met Francesco Zuccarelli and seems to have made the decision to switch professionally from portraiture to landscape.

Wilson arrived in Rome in late 1751, at a remarkably propitious moment. It coincided with a rare period of European peace, following the conclusion of the Austrian War of Succession and the city was filled with painters from across the Continent, as well as a large number of acquisitive Grand Tourists. Wilson also befriended the antiquarian Johan Joachim Winkelmann and the neo-classical painter Anton Raphael Mengs, who painted Wilson’s portrait. He gravitated towards the great French landscape painter Claude-Joseph Vernet, but we know he also worked in the circle of the French academy in Palazzo Mancini, spending time with its resident director, Charles-Joseph Natoire who led sketching parties into the campagna.

Shortly after his arrival in Rome, Wilson developed the practice of making studies en plein air, ranging around Rome and its environs to record vistas, details of archeological remains and, more rarely, studies from nature. These sketches proved an invaluable resource for producing finished drawings and oils of Roman views. Wilson’s artistic innovation was the synthesis of the classical landscape tradition of Claude Lorrain and Gaspard Dughet, with a topographical verisimilitude. This was a formula that was to have profound effects on European landscape painting, in essence bridging the two disparate practices of topography and imaginary landscape, endowing views of real places with all the feeling, effects, and grandeur of the invented setting for a scene from Virgil or Tasso. Wilson’s contemporaries appreciated the innovation. Wilson’s pupil, Joseph Farington, noted: ‘wherever Wilson studied it was to nature that he principally referred. His admiration of the pictures of Claude could not be exceeded, but he contemplated those excellent works and compared them with what he saw in nature to refine his feeling and make his observations more exact; but he still felt independently without suffering his own genuine impressions to be weakened.’[1]

This process of refinement and exact observation was driven by Wilson’s obsessive practice as a draughtsman. This impressive sheet shows a sinuous and sculptural stand of chestnuts and was clearly meticulously observed on the spot. The scale and ambition of this sheet suggests it was made to be used by Wilson in one of his painted landscapes, the complex architecture of branch and foliage is similar to the stand of trees which frame Wilson’s great view from Monte Mario commissioned by William Legge, 2nd Earl of Dartmouth and now in the Yale Center for British Art. Careful inspection of the Yale painting shows the effective use Wilson made of his plein air studies; the trees are convincingly organic and show no sign of stylisation or arboreal shorthand. In this respect, Wilson’s method directly follows that of Claude, who made a series of meticulous and beautifully worked studies of trees in and around Rome.

Wilson worked almost exclusively in black and white chalk on toned paper, a practice which grew out of his observation of contemporary French artists. Wilson’s greatest Roman drawings can be compared with contemporary French drawing, such as the sequence of studies made by Jean-Baptiste Oudry at Arcueil between 1744 and 1747. Highly worked drawings such as the present boldly worked sheet show how Wilson came to master the medium: observe the way the blended – or stumped – passages capture the volume of the trees foliage and the touches of white chalk show the light passing through the canopy. Wilson told Ozias Humphry that ‘the best and most expeditious mode of drawing landskips from nature is with black chalk and stump, on brownish paper touched with white.’[2] It was with this in mind that Humphry wrote from London to Francis Towne in Rome in April 1781: after sending regards to friends Jones and Pars in Rome he says, ‘I shall esteem it a great favour if you would be so obliging as to bring me three or four pounds of Black Italian Chalk but pray take care that it is really good, smooth & Black because we have an indifferent sort in great abundance here.’[3] Wilson’s use of monochrome reflected his desire to internalise the form of the objects he was observing, without the distraction of colour. It was a method he later recommended to his pupils. Thomas Jones recorded that he was encouraged to work only in ‘black and white chalks on paper of a Middle Tint’ adding ‘this, he said was to ground me in the Principles of Light & Shade, without being dazzled and misled by the flutter of Colours – He did not approve of tinted Drawings and consequently did not encourage his Pupils in the practice – which, he s’d hurt the Eye for fine Colouring.’[4]

Only one comparable drawing by Wilson survives. A sheet depicting the so-called Abra Sacra, now at the Yale Center for British Art. This careful drawing recorded a famous plane tree – which had a hollow trunk which could accommodate a dozen men - on the banks of lake Nemi, one of the volcanic lakes situated in the Castelli Romani, the hills to the northeast of Rome. Close to Nemi is the village of Rocca di Papa, the subject of one of Wilson’s drawn views made for Lord Dartmouth, and the location of a famous grove of chestnut trees. The present sheet clearly dates from early in Wilson’s time in Rome and may well be contemporary with the Dartmouth commission and depict the trees at Rocca di Papa.

Preserved in exceptional condition, the surface of the chalks is undisturbed and particularly fresh, this drawing is a masterpiece of European eighteenth-century draughtsmanship. Wilson’s drawings were collected and venerated by his contemporaries and celebrated by succeeding generations. John Constable praised his singular vision – ‘he looked at nature entirely for himself’ – and the young Turner veraciously copied Wilson’s work.[5] Wilson imparted a profound emotional quality to his Italian drawings and in the complex and beautifully captured forms of these trees, the present sheet prefigures the great Romantic nature studies of the first half of the nineteenth century.

References

- Ed. Kathryn Cave, The Diary of Joseph Farington, New Haven and London, 1982, vol.X, p.3532.

- Quoted by David Solkin in ‘New Light on the Drawings of Richard Wilson’, Master Drawings, Winter 1978, vol.16, no.4, p.410.

- Richard Stephens (ed.), Correspondence of Francis Towne (1739-1816) online at http://francistowne.blogspot.co.uk Ozias Humphry, from Newman Street, London, to Francis Towne ‘au Café Anglois/ a Rome’, dated 17 April 1781.

- Ed. Paul Oppé, ‘The Memoirs of Thomas Jones’, The Walpole Society, 1946-8, vol.XXXII, p.9.

- For Constable’s comments on Wilson see ed. R. B. Beckett, ‘John Constable’s Discourses’, Suffolk Record Society, 1970, vol.XIV, pp.66-67. Turner’s studies after Wilson see ed. Andrew Wilton, J.M.W. Turner The Wilson Sketchbook, London, 1988.